Ghatam Instrument Overview

The ghatam is an ancient Indian percussion instrument that plays a large part in South Indian Carnatic classical music tradition. Other names for this instrument include bada, ghara, matka, and noot. The ghatam is considered an idiophone because the whole of it vibrates to produce a sound when struck—unlike membranophones which have drum heads that are struck, like the tabla or mridangam.

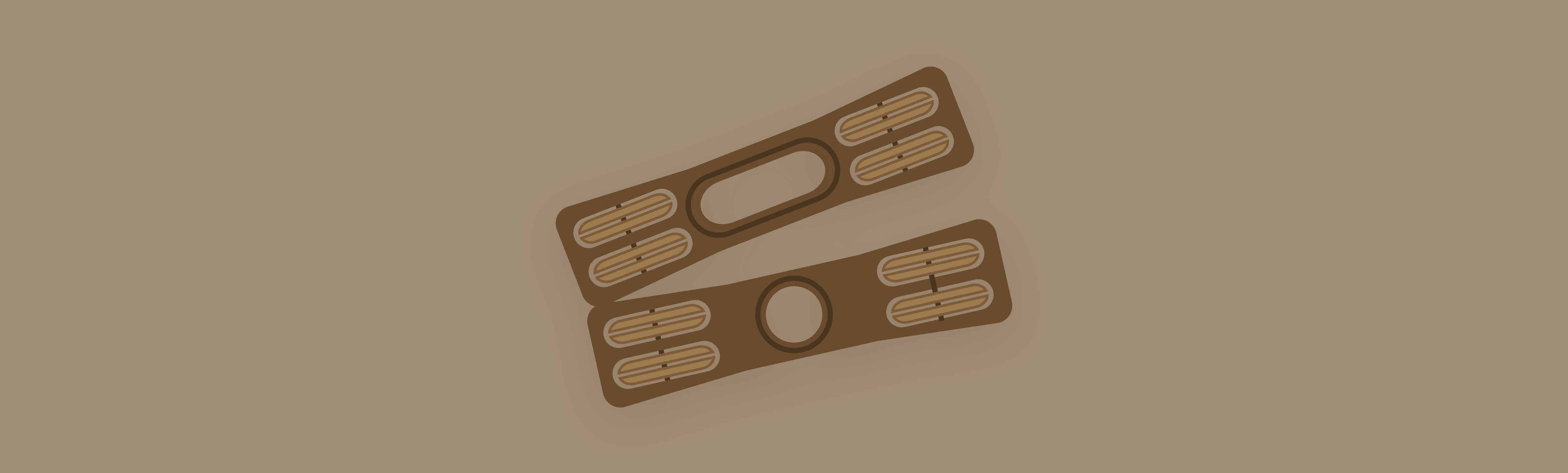

The ghatam instrument itself is a rounded, earthenware pot with a narrow opening at the top. The mouth of the pot has an outer rim above a narrow neck. The body, neck, and rim of the instrument each produce a different tone when struck. The ghatam is known for its deep, sometimes metallic sound in various pitches and often accompanies the mridangam in concert performances or percussion ensembles.

Although the ghatam looks like a regular clay pot, it is specially made to be an instrument. The instrument comes in many different sizes and is made from a mixture of clay, mud, and sometimes metals (typically brass or copper). The thickness of the pot must be even to produce a quality tone. Ghatams are made in many places in India but most famous are those made in Manamadurai, which produces ghatams that are thicker and heavier with a distinct sound.

The ghatam is played with the fingers and palms of both hands—producing fast, complex Carnatic rhythms. Ghatam music provides the ‘heartbeat’ for many of the pieces it accompanies. The instrument is positioned either on the lap of the seated player or in front of them on a chutta or bira, the ring-shaped cloth base for tabla. In South Indian technique, the opening is pressed against the player’s stomach.

History of Ghatam

Although there are many clay pots that have been used as instruments all over the world throughout history, none have maintained the popularity and sophistication of the ghatam. Ghatam meaning comes from the word <i>ghata</i> in Sanskrit, meaning pot. The ghatam as an instrument was first described by Sage Valmiki in the ancient poem Ramayana, dated roughly 500 CE. The sound the ghatam makes when played has been described in several other Sanskrit texts on rhythm and music, including the Tamil text Silappatikaram from around the same period of time. It is thought that the first ghatams may have had skins covering the opening, making them an idiophone and a membranophone, but since the folk music practices of the 6th century to now, the ghatam has not had a membrane stretched across the mouth of the instrument.

The ghatam began as a folk instrument in several parts of India and remains a prominent part of many folk traditions today, particularly in Punjab. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the ghatam was included in South Indian Carnatic classical music performances. In the 1800s, Polagam Chidambara Iyer was said to have been the first concert ghatam vidvan (a master of one's art), introducing the folk instrument to Carnatic concerts. Years later, Palani Krishna Iyer is said to have developed rhythm patterns and playing techniques specific to the ghatam. However, tabla techniques are still used by some contemporary ghatam players.

In Carnatic music, the ghatam is considered an additional, or secondary, instrument that is meant to back up the mridangam. However, over the last 50 to 100 years the ghatam has gained increasing popularity, becoming a more prominent solo instrument, as well. In addition to traditional and classical Indian music, the ghatam is finding popularity abroad. In the last few decades, this unique percussion instrument has become prominent in many world fusion genres, as well as rock and jazz music.

Types of Ghatam Musical Instrument

Ghatam musical instrument used in South Indian Carnatic classical music has some minor differences because of the different makers but are mostly similar. They come in many different sizes but have the same colouring and dimensions to maintain the quality of sound. The red/orange colour of the ghatam is due to the clay, metals and glazing process.

Most South Indian ghatams for Carnatic music are made in either Chennai or Manamadurai. Those made in Chennai are called Madras ghatam and are typically thinner than the Manamadurai ghatam because they are made from only clay. Madras Ghatams are considered easier to play than their much heavier counterparts. For this reason, the Madras ghatam is recommended for students who are just starting out learning ghatam music. Manamadurai Ghatams are made with brass or copper pieces, creating a very distinct, deep, metallic sound.

The North Indian version of the ghatam, called the ghara, is very similar but has thinner walls and is blue/gray in color due to graphite being used in the construction, along with clay and other metals. These are heavier than Madras ghatams but lighter than Manamadurai ghatams. Gharas are typically played with mallets instead of the player’s hands.

The matka is the version of ghatam popular in Gujarat and Jaipur. Unlike other ghatams, the matka doubles as a cooking or storage vessel when not being used as an instrument. Players of this type of ghatam may wear metal rings on certain fingers to produce sharper, staccato sounds.

Playing Techniques

Playing style varies by location and teacher. In Carnatic classical music, where the techniques are more standardized, the instrument is played with the mouth of the pot pressed against the stomach. Changing the pressure of the pot against the stomach changes the resonance and pitch of the sound. In other styles, such as North Indian tradition, the pot is typically played upright.

South Indian Ghatam players use the hand positions that are typical of other percussion instruments to produce the complex rhythms that Indian percussion style is known for. While the ghatam has specific positions for playing, it also borrows from mridangam and tabla hand positions. The body, neck, and rim are played with multiple fingers, palm, and wrist positions but the ghatam makes another unique sound, as well. When the mouth of the pot is struck with the palm, it creates a low resonate sound.

The ghatam is also a very popular instrument for improvisation and movement—to the delight of many audiences. The ghatam is the only instrument that changes position while being played, as the musician may change the direction of the instrument to achieve a different pitch or tone. Some ghatam vidvans even throw the pot in the air and catch it while maintaining the rhythm to entertain audiences. It is said that ghatam players were the jesters of early Carnatic performances.

Ghatam Mechanics

Each ghatam has a singular pitch of its own because it depends on the size, thickness, and temperature the pot is fired at. The larger and heavier the pot is, the lower the pitch is—while smaller pots have a higher pitch. The pitch can be altered slightly by applying water or clay putty to the inside of the pot but this practice is not exact and requires repeating to maintain the difference. For this reason, a professional ghatam player may have several different sizes for a single performance.

The ghatam has three main playing areas, the upper, middle, and bottom portions, each of which has their own distinct sections. When a student takes ghatam lessons, they learn how to speak and then play the different notes (called konnakol in Carnatic classical music and bols in Hindustani classical music) and where to play them to achieve the desired sound. Altogether, there are seven playable sections of the ghatam:

- Tha

- Thi

- Thom

- Nam

- Ti

- Kun

- Na

Notable Ghatam Players

There are many famous ghatam exponents, past and present. Below are some of the most well-known contemporary ghatam players from around the world.

- Ganesh Anandan

- Ghatam Giridhar Udupa

- John Bergamo

- Gurpreet Singh Mann

- Glenn "Rusty" Gillette

- Karthick Subramaniam (View his course)

- Kottayam Unnikrishnan

- S. Karthick

- Sukanya Ramagopal

- Sumana Chandrashekar

- Suresh Vaidyanathan (View his course)

- T.H. Subash Chandran

- T.H. Vinayakram

- T.V. Gopalakrishnan

- Trichy Sankaran

- Tripunithura N. Radhakrishnan

- Udupi Balakrishnan

- Umayalpuram K. Sivaraman

- V. Selvaganesh

- Vikku Vinayakram